23 Dec GAA Talent Academy and Player Development Report- A Snapshot- by Brian Cuthbert

By Brian Cuthbert PhD – co-author of the TAPD Report

Some of you may have noticed that the GAA has recently launched a wide-ranging report regarding Gaelic Games academies and their interactions with player development at youth level across the organisation. If you have had the opportunity to read the report, you should hopefully see the necessity for the specificity and depth of the recommendations contained within it. You would also have noticed the findings in relation to the many positive activities that are happening at academy level within youth Gaelic Games in Ireland. Chief amongst them was the absolute passion stakeholders have for the GAA within their own county. The level of altruism and volunteerism across all levels of the Association is huge and at academy level players certainly benefited from the deep rooted desire for county advancement from individual stakeholders. This desire was supported in many instances by good coaching, quality physical infrastructure and experienced fulltime coaching staff. The GAA has many credits lodged firmly in the bank in many counties in terms of engagement, appetite for work and commitment.

Despite these many credits, if you happen to be involved in the GAA, you may have felt for some time that there is a need for change around philosophy when attempting to develop potential in our youth players. Maybe if you are involved in other sporting pursuits, you may also have the feeling that something is amiss in how your sport develops potential into talent? Maybe your sport also has difficulties in retaining players or transitioning players through to adult competitions? Maybe your sport is attempting to find the very best players at a very young age and give them the ‘special treatment’ so that they can become a superstar in the future? Maybe your sport has difficulties with managing the crossover of individual players between teams and appropriate levels of communication between coaches? Maybe your sport doesn’t provide enough games for some children and too many for others who may be deemed talented? I doubt that the GAA is alone when it comes to these issues. So at the outset, if you do get a chance to read the report, you will notice that the central tenet running through it, is the necessity for synergies between stakeholders and cultivating within them a developmental long-term philosophy that fits easily to the values of the GAA. By doing so, it is hoped that many of the challenges identified within the report will be addressed.

GB Hockey frame such a philosophy well by using the slogan ‘the end in mind’. This promotes the concept of player development as a long-term process that has connotations of a journey. That’s exactly what this report envisages development to be; a journey with many ups and downs but one in which the player or athlete is supported on throughout. It is this context the major recommendations were developed. These include 1) new governance structures; 2) a new player pathway framework; 3) nuanced educational opportunities for all stakeholders aligned to the framework; and 4) overt structural changes to competition. These recommendations are based on the analysis of over 1000 interviews with various GAA stakeholders inclusive of coaches, players, teachers, parents, administrators and fulltime GAA staff. This analysis provided the committee responsible for conducting the review with a clear manifesto – provide stakeholders with clarity around a development process which is rooted in the context of Gaelic Games and Irish culture, i.e. our sense of identity and place.

Such a manifesto is timely as sport in general has undergone a process of globalisation and professionalization; sport is becoming the same all over the world regardless of context. The difference in this instance is that the GAA is an indigenous amateur sporting organisation and a commodified, professionalised approach is very much at odds with its associated ideology. However, these societal trends have led to many professionalised practices entering into the GAA domain especially in the areas of sport science, coaching methodologies, training facilities and talent identification and development systems. Some of these practices were identified as real positives by stakeholders and certainly have their place in player development within the Gaelic Games pathway. However, the analysis of data within the review process would suggest that many stakeholders within the GAA have adopted many of these trends unreservedly, without question and without ever considering the unique social and cultural complexities inherent within the Association. Our context is based on volunteerism, limited resources and representing multiple teams which is far removed from the context of professionalised sport.

Simply put, the GAA is complex. Such complexity, in the context of this report, was most pronounced within the actual governance and operation of the various development systems of individual counties. Despite the limitations of resources evident surrounding the academies, academy personnel have attempted to provide ‘the next level’ of development to prospects. This ‘next level’, as referred to by many stakeholders, has direct connotations to a mirroring of the professionalised approach now prevalent at elite senior levels in Gaelic Games. Youth players and their coaches, in turn, believe that in order to eventually transition to elite level senior level, it is imperative that they are provided with such an approach. However, as has been reported in other sporting domains (e.g. Norwegian handball), the complexity created by the professionalisation of the development approach, has resulted in a change in learning conditions for talented youth athletes.

In the context of Gaelic Games, this change in conditions has instigated a number of negative implications for talented youth players that are characterised by a lack of synergy between coaches, inappropriate workloads and practices as well as environments where players had little control. Simply put, we think we are providing players with what they need to become elite adult players later in life, but in fact we are creating more barriers for them in terms of their developmental journey. It therefore could be argued that we have thus far failed to capture a holistic, integrated and longitudinal understanding of the athlete pathway and instead have concerned ourselves with attempting to provide young talented athletes with ‘a professional approach’.

Such an approach also stems from the beliefs stated by some academy administrators and coaches, that there is a necessity to provide prospects with an approach which has similarities with that provided by other sporting organisations e.g. The FAI run the Kennedy Cup (a national cup competition) at u14 so we must offer the players something similar in the GAA. This can be related to the inclination of policy implementers to display a form of legitimacy in relation to utilising similar strategies, techniques and vocabulary within and across sporting domains i.e. we must be seen to be doing it because other sports are doing it. The desire for legitimacy in this instance impregnates the ideas, values, and conditions underpinning the organisational culture of Gaelic Games. The GAA is and always has been different. It cannot be a clone of the other sporting bodies here in Ireland or elsewhere. Now more than ever before, it needs to stand alone.

In order to control and direct such legitimate aspirations at ground level, it is imperative that the GAA provides a responsive governmental structure for its developmental pathway stakeholders to operate within. This is exactly what the report sets out to do through the creation of new governance structures; provide levels of responsibility and accountability that heretofore were not common place within the Gaelic Games player development domain. The report recommends that the GAA appoint Player Pathway, Coach Education and Sport Science managers at both national and provincial levels. It is hoped that these positions would be mirrored within counties (maybe by realigning the roles of current staff or by appointing qualified volunteers). It is envisaged that these appointments would bring clarity to practice but also bring connection between grassroot coaching behaviours and policy development in GAA headquarters in Croke Park. As such, the report is suggesting that Croke Park needs to stretch out its tentacles and reach out into every corner of the world where GAA is played. Our stakeholders want direction, they want clarity and they want to be led.

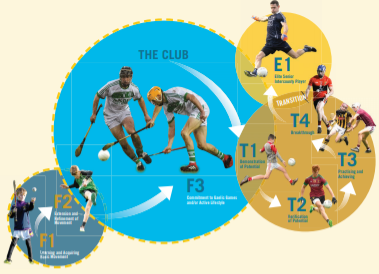

The report also recommends that such a governmental structure should be supported by empirical and theoretically based guidelines for practice so that academies can move beyond prescriptive models of talent development (e.g. The Standard Pyramid Model of Talent Development) and adopt a more inclusive approach to providing players with potential with the opportunity to experience the academy environment. Entitled the Player Pathway Framework, the report has attempted to provide such structure and guidance whilst also positioning the club at the very epicentre of player development (classified as the F phases within the Framework). This is where the majority of the players reside and at present, due to the aforementioned professionalization of sport, they seem to be the ‘forgotten people’. Whilst in its infant stage at present, the Framework is a clear representation of the envisaged player pathway. In time, it will be inclusive of the features of best practice at its various phases and how they can be implemented in the applied settings of GAA clubs, schools and academies around Ireland and the world. In doing so, the GAA might gain a level of control within the development context and contribute to a positive personality development of the majority of players and thus engage them within the association for life e.g. provide players with the right support at the right time.

Figure 1: The GAA Player Pathway Framework

The Player Pathway Framework’s staged approach ensures that when young players are initially attracted to our Games, they are exposed to appropriate practices that are focused on multisport fundamental movement skills. Such a focus readies players to transition easier onto the next stage of the Foundation Phase, F2, since they will be equipped with the necessary foundational skills to allow them to become competent in developing the actual technical skills necessary to facilitate an enjoyable playing experience. Once children transition to Foundation Stage 3, it is vital that they continue to be exposed to quality environments that are inclusive of empowered coaching aligned to an appropriate games programme. Such an alignment between the game, the player and his environment ensures that players are intrinsically motivated to play and stay with the GAA. This synergy is even more crucial since F3 coincides with a player’s first exposure to competition. It is vital that players feel valued and are part of environments in which they are equally challenged and supported regardless of their levels of ability.

Retaining, transitioning and nurturing our players is central to ensuring that the GAA continues to influence the lives of people in local communities across Ireland as well as in our overseas units. This involves a co-ordinated approach from many at club level. It must be an enjoyable journey from a child’s first involvement with the club nursery to the last time donning the club jersey at adult level many years later. At various junctures, the player will need to be supported in order to transition to another level within the club. That is exactly what our Player Development Framework sets out to do; provide the right support at the right time to players so that they transition through a supported developmental pathway and remain involved in the GAA for life.

Along this pathway, some players who are deemed to have potential may enter the Talent Phase of development. Within this phase, this potential will become verified and ultimately over time, some players will make a breakthrough into the Elite Phase, E1, to become senior inter-county players. It is vital that messages and actions of Talent Phase stakeholders are founded in the knowledge that the club remains at the epicentre for a player’s development. These practices must be viewed as an add on to the work done at club level and not the exclusive initial entry point for inclusion in the E1 phase later in life. Ensuring that this philosophy becomes the norm in the Talent Phase so as to safeguard the position of the club will not be easy. Mistakenly, people believe that we must find the best players early and train them in a certain type of environment that is based on a professionalised, elitist approach. This model implies that players are extracted from clubs and are pitted against others from a young age in a contest of survival of the fittest. Scientific evidence would argue that this approach is very much flawed.

Instead, by creating greater alignment between the Talent Phase and Foundation Stage 3, both phases can become more mutually inclusive of each other. This will involve greater co-operation and trust than heretofore between Gaelic Games coaches which in turn will develop greater synergies between stakeholders. This realignment will also allow coaches the opportunity to make more informed decisions on players of potential as late as possible in their developmental journey. Such an approach not only limits the level of deselection currently in existence within the Talent Phase but also ensures that players, because of their age and the messages they have received through their Talent Phase involvement, can better self-regulate the emotions deselection brings.

Crucial to bringing about these changes and copper-fastening the club as the most central component in the player pathway will be the introduction of an aligned Coach Education Framework. Through this framework, coaches will, in time, develop a more holistic view of development and become more reliant on each other so as to develop a more co-ordinated player pathway for each player under their care. Once individual units in county and school’s games administration bodies, provide players with a functional and nuanced games programme, it is envisaged that both the Player and Coach Development Frameworks will combine to create environments surrounding the player that are supportive, challenging and exciting.

Providing such environments at club level is going to become our ultimate challenge as an organisation. However, we view these Player Pathway Frameworks as the roadmap to making sure that we stay on course and with the help of all stakeholders, we are certain we will ultimately reach our destination. This destination is a point in the future whereby through a process of education, coaches will put the needs of their players before their own egos and have a clear understanding that they must support the player by communicating with the other coaches involved with his development. Similarly, it’s a point in the future whereby players have a co-ordinated and appropriate games programme scaffolding their development so they no longer are exposed to over-activity and possibly burnout. The future of player development in the GAA can be one where the player can feel that he is in control, that he can make decisions for himself regarding his own development. The player will feel supported through these decisions by the various stakeholders involved in his pathway, who in turn will be feel supported by the Frameworks. Finally, the destination point is a future whereby development at youth level in Gaelic Games has the person as its focus, drives the values of the GAA by being firmly rooted in the club and keeps ‘the end in mind’. Is this too much to ask from ourselves?

John kenny

Posted at 16:34h, 24 DecemberHow in God’s name has something so simple as a few lads or ladies running about after a bag of wind or cork and sometimes with a stick (hurley) become so complicated / complex and so demanding. Why can the powers that be not allow the young players to actually PLAY the games. The games are in intensive care trying to survive and the solution is to super complicate them.

R McNeill

Posted at 01:37h, 25 DecemberHi

Was the “report” produced by volunteer/volunteers .

Thanks

R

Micheal Kennedy

Posted at 09:07h, 25 DecemberThe problem is complex so the solutions look difficult and complex and perhaps unworkable.But it’s worth trying for everyones sake.