04 Sep Physiological Fitness Training for Team Sports – By Ryan McLaughlin MSc

By Ryan McLaughlin BA MSc – Sports Scientist at STATSports, Performance Coach with Donegal Senior Hurling Team.

Different, novel, scary, anxious – just a few of the words that come to mind when trying to describe the current situation we have all been subjected to with the COVID-19 or CoronaVirus pandemic making its way across the globe.

Fitness, maintenance, injury, championship – just a few of the words or topics of conversation popping up in WhatsApp group chats or Zoom calls from teams all over Ireland and further afield.

None of us could have anticipated the lockdown and the chaos that ensued around returning to sport, between the training ban and postponement of Championship games throwing our training plans out the window. While everything has changed so much in the past 6 months, absolutely nothing has changed for the players. The focus for anyone with aspirations this season is still to keep fit and develop physically to support the style of game they want to play. Fortunately, most of us have a pre-season of some sort completed with most clubs preparing for league games prior to lockdown.

In this article I am going to take you through some considerations around what conditioning qualities to focus on training during your individual sessions with game-based performance in mind. Firstly, before any practical plans can be made, we need to look at the demands of the sport – based on position, age group, tactical influences and so on. Gaelic games are intermittent in nature with unpredictable work:rest ratio’s & work demands that stem from fast paced transitions, counter attacks and turnovers (1).

Aerobic Capacity

Power, speed and the ability to repeat intense efforts are key to performing well in the game. However simply training intense efforts will not provide adaptation to the full potential. The factor of fundamental importance to repeated efforts at consistently high levels is down to the aerobic capacity of the athlete. Research has shown a significant correlation between a high aerobic capacity and the ability of an athlete to firstly recover quickly from intense efforts and secondly the ability to sustain a higher volume of these intense efforts throughout a session or game (2). So, while the product of our training results in repeated sprint efforts during gameplay, we first need to provide the physiological foundation for this to take place. The lockdown is a great opportunity to work on this aerobic capacity from both an on-feet and off-feet perspective. For a game that is played on-feet, there is no off-feet substitute that can match the demands of on-feet conditioning, but it can provide an aerobic stimulus while allowing the lower portion of the body to recover and adapt from previous training.

Anaerobic / Glycolytic Capacity

The capacity for anaerobic work is important from a game specific perspective as well as a conditioning view. Generally anaerobic-glycolytic efforts can be classed as efforts up to 3 minutes in duration based on each individual’s physiology. The anaerobic or glycolytic energy system will come into play during extended periods of intensity such as attacking, defending and counter-attacking. While not close to the maximal speed of a sprint, anaerobic activities are usually performed while moving at high speeds (3). Training to develop anaerobic capacity should incorporate work bouts of between 30 seconds and 3 minutes, the key to emphasize when training to develop anaerobic capacity or power is effort. The athlete needs to be pushing themselves to a near-maximal effort level. The fact that the exercise is of a duration longer than 30 seconds means that they will physically not be able to sustain a ‘sprint’ speed, so effort is fundamental. Work: rest ratios are tricky to recommend and come down to an athlete’s ability a lot of the time, generally between 1: 1 and 1: 2 work: rest ratio is sufficient to allow recovery depending on the duration of the effort.

Max Velocity Exposure / Max Speed

Maximum speeds are a necessity for athletes across the board in any team field sport. The scenario will arise in a game when you are literally racing against an opponent to score or just to gain initial possession of the ball. If you haven’t been exposed to regular high speeds prior to this, there is a high chance of either of the following happening; you will not get to the ball first or you may injure a muscle in your hamstring. Max speed exposures are crucial along with adequate running mechanics to improve performance, but an overlooked factor is their relevance to injury prevention. Sprinting maximally is the only exercise that produces a sprint specific amount of muscle activation in comparison to other eccentric hamstring strengthening exercises which only measure up to between 18 & 75% of the required activation (4).

The main point of this section being sprinting can act as a vaccine to sprint related hamstring injuries if loaded adequately across a training week or block (5). A key consideration for achieving a max speed however is distance. You physically can’t achieve your max velocity over 5-10 meters, this would only be classed as an acceleration. To reach maximum speed you need at least a 30-meter effort to reach close to top speed. You should aim to achieve >95% max speed with each effort (5).

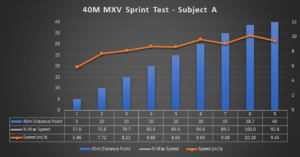

Below is a visual representation of when an athlete reached various % markers of his max speed over a 40m sprint, this data is taken from my own work during a recent testing session.

Accelerations, Decelerations & Change of Direction

Possibly the most game specific quality that should not be neglected during the period of lockdown. Quickly moving, quickly stopping and quickly changing direction are movements that the tendons of the body adapt to with adequate training that you may pick up across football or hurling game-based drills where there is a reactive element. However due to the lack of personnel with individual training it is very easy to forget about these components.

If you step back on to the field down the line to play a sport which is reactive in nature and has high levels of accelerations, decelerations and changing of direction but you have only focused on straight line running, your body will not be able to facilitate these demands. In game play, accelerations and decelerations at speeds of at least 2.5m/s/s are evident, so the body needs to be able to move and stop reactively at these speeds as a bare minimum. From a sport specific perspective, it would be preferable to have drills for these qualities be as reactive as possible but as there is not collective training, that is not always easy.

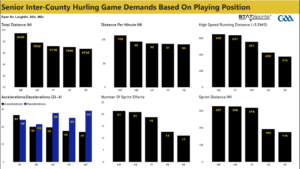

Game Demands

Game demands should be a heavily weighted reference point when planning training volume and intensity of any given training block or in the lead up to competition. As coaches it is our job to ensure that the players are robust enough to handle the demands of the game but also to be able to perform to their potential. Players should not be subjected to game demands during every session but implementing thresholds based on percentages of these demands is certainly a good idea. See below for a sample of inter-county hurling game demands, it is important to note that this is intercounty level but may serve as a good comparison point.

Monitoring Training Load Individually

While coaches and managers may not be present to monitor the effect the training session has on each player, players can still monitor external and internal response to training by themselves.

Firstly, by properly measuring and marking out any drill that they are going to complete, they will be able to quantify the volume or total distance of each effort. By timing each effort and dividing the distance covered by the time completed in seconds, they can find their average speed during the drill. For example, if a player runs 100m in 20 seconds, they can infer that their average speed during that effort was 5.0m/s. This can be done with all reps of each running exercise to check if there is any sort of drop off or if they are able to maintain the same level of physical output throughout.

Secondly, internal response to training can be quantified (subjectively) by completing daily wellness questionnaires around muscle soreness, sleep quality, stress levels as well as the session’s rating of perceived exertion (sRPE) on given training days. This data can then be compiled in a database on Microsoft Excel or similar packages to provide a better picture of load for coaches who are not physically present at the session.

Cost Effective GPS Solutions

GPS (global positioning systems) units can be worn to provide an extremely accurate measure of physical output during training sessions. Until recently, GPS solutions for team’s have been categorized as expensive. STATSports have recently released the Coach Series product which is aimed at teams with low budgets but big aspirations.

The concept of the coach series is on the provision that each player purchases their own STATSports Athlete Series unit which is the consumer version available to the general public at a fraction of the cost of the same GPS unit that professional teams use. Each of these players simply link their STATSports Athlete Series account to the coaches account and the coach can see all activity completed during individual training during the lockdown.

Benefits of having GPS available to teams and players are countless, particularly in the team environment they can;

- Provide a range of metrics applicable to the sport as opposed to general fitness trackers worn on the wrist. There are a range of metrics available to the coach at the touch of a button such as; Total Distance, Distance Per Minute, High Speed Running, Sprints, Max Speed as well as providing detailed positional and heat maps.

- Allow coaches to compare players against each other based on their physical performance.

- Ensure intent of effort as the player knows the coach will be interpreting the data after the session.

- Allow coaches to get an accurate view on loading of a session or a block of sessions.

- Allow coaches to establish a database of game demands specific to their team in competition.

- Promote the competitive nature of team sport even in a lockdown situation with functions such as a team leaderboard based off metrics such as; Total Distance, High Speed Running Distance and Max Speed.

Conclusion

To conclude, the current situation is far from ideal and one which very few in the sporting world could have anticipated a few months ago but if we focus on the controllable factors, preparation for the return to sport doesn’t have to cease.

Game demands should always be prioritized and referenced heavily when planning training throughout the year. The goal of training for your sport is to be able to perform in your sport, this is the main goal no matter what. All the above considerations are based solely from a conditioning perspective, a sufficient strength training and robustness program should not be neglected during this period either.

If there are any questions around any of the above, please feel free to get in contact with me on social media or via email.

Author Details

Ryan Mc Laughlin, BSc, MSc.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ry4nmclaughlin

References

- Gamble, D., Bradley, J., McCarren, A. and Moyna, N.M., 2019. Team performance indicators which differentiate between winning and losing in elite Gaelic football. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 19(4), pp.478-490.

- Ostojic, S.M., Stojanovic, M.D. and Calleja-Gonzalez, J., 2011. Ultra short-term heart rate recovery after maximal exercise: relations to aerobic power in sportsmen. Chin J Physiol, 54(2), pp.105-110.

- Bangsbo, J., Iaia, F. M., & Krustrup, P. (2007). Metabolic response and fatigue in soccer. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 2(2), pp111.

- van den Tillaar, R., Solheim, J.A.B. and Bencke, J., 2017. Comparison of hamstring muscle activation during high-speed running and various hamstring strengthening exercises. International journal of sports physical therapy, 12(5), p.718.

- Edouard, P., Mendiguchia, J., Guex, K., Lahti, J., Samozino, P. and Morin, J.B., 2019. Sprinting: a potential vaccine for hamstring injury. Sport Performance & Science Reports, 48, p.v1.

No Comments