27 Aug Deceleration & Change of Direction (COD) – By Caoimhe Morris MSc

By Caoimhe Morris BA MSc – Head of Education at Deely Sport Science

Jacob Stockdale, Sabrina Ionescu, Kylian Mbappé and Sarah Rowe are all extremely talented sportspeople with the ability to leave defenders in the dust. Their ability to decelerate, control force and re-accelerate in a short period of time is what gets them past defenders in a game, and is why they are considered to be both talented athletes and nightmares to defend against.

Credit ©INPHO/Ryan Byrne

The ability to trick a defender into thinking you are moving one way, only to accelerate in a different direction is a vital and useful skill in almost every team sport. Although deceleration and change of direction (COD) can come hand in hand, tricking a defender is not the only use for them. We know that deceleration occurs more often than acceleration in team sport due to the unpredictability of the game (Harper et al, 2019). The ability to control one’s mass and force to the point of stopping is necessary in every sport. While an Olympic sprinter will not engage in change of direction, they will engage in deceleration unless they wish to maintain a max sprint for the rest of their life!

Deceleration

We engage in deceleration (how quickly we can reduce velocity with respect to time) numerous times a day, in both normal life and sport. While it is a natural movement for most, it is also important to understand the mechanics of deceleration and ensure our players are slowing down safely. The task of slowing down is often under a short time constraint and so experience & understanding in such a task is an important skill that all athletes should hold.

“The forces applied to the body when decelerating can be exceptionally large in magnitude, especially when the time over which these forces must be absorbed is small” Hewit et al, 2011.

Our ability to decelerate efficiently (i.e with proper mechanics in the appropriate time) is dependent on a number of physical capabilities. By modelling training around these capabilities in order to enhance the athletes’ ability to perform these tasks to their full potential, we will help improve athletic ability and reduce the risk of injury. Efficiency in deceleration is dependent on the athletes:

- Eccentric Strength

- Neuromuscular Control

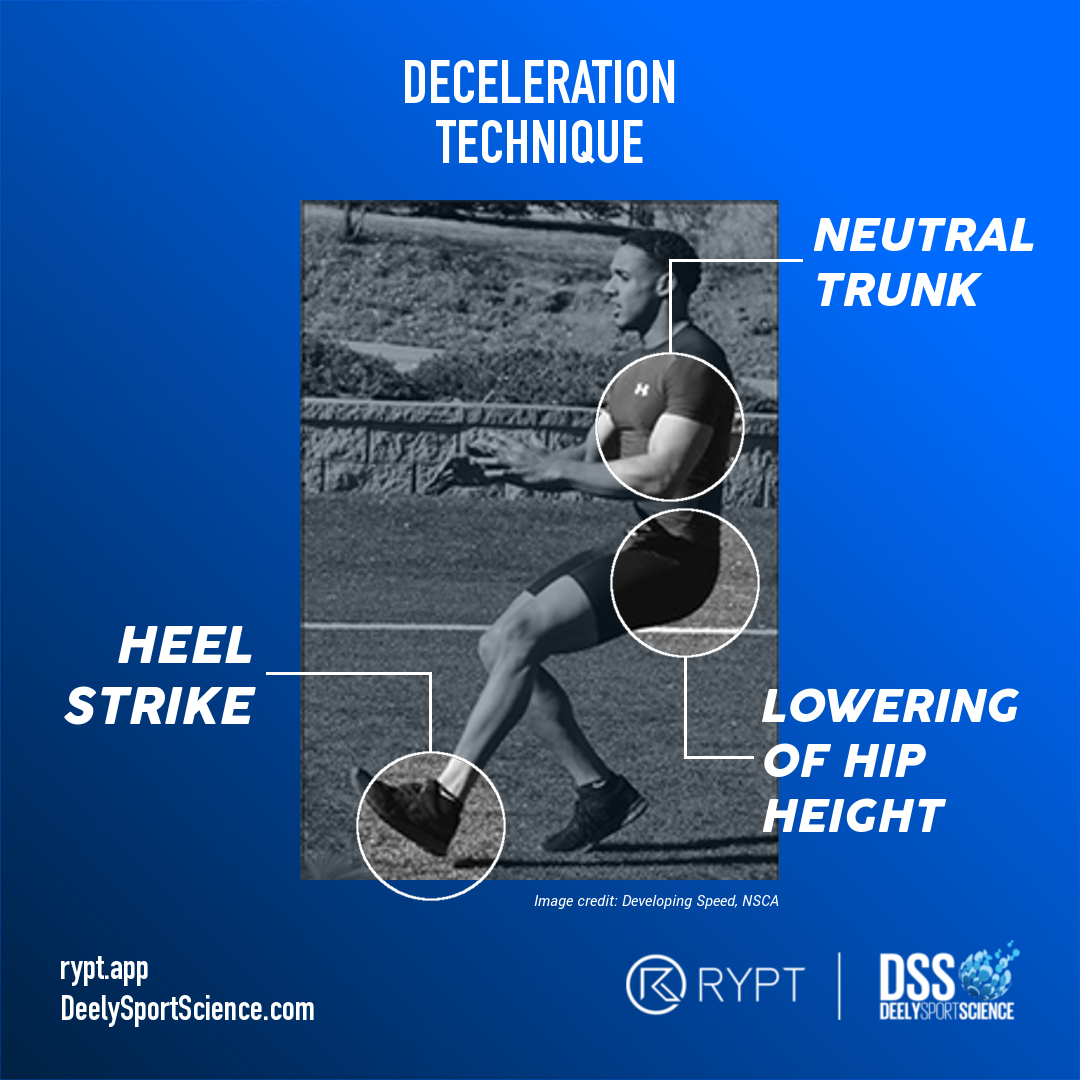

The mechanics of deceleration are centred around the lowering of ones mass with minimal trunk change. Optimal linear deceleration technique involves

- Heel strike to full foot contact

- Lowering of hip height

- Neutral trunk – i.e minimal trunk change (flexion, extension ot rotation) to that of acceleration

Image 1: Linear deceleration (Sheppard, 2017)

A term coined by Jonas Dodoo (Speed Works Training) which nicely describes this sequence of events is “Quiet Sitting”. The athlete lowers & controls their mass over time into a position similar to that of sitting on a chair, i.e back straight, knees bent and hips slightly higher than knees. In order to ensure the athlete can carry out this task efficiently we must ensure they have the strength and control to do so. This can be developed via the training suggestions below.

Training to improve deceleration ability

- Strength

- Eccentric variations of lifts – Bilateral & Unilateral (Eccentric squat, Single-Leg RDL, etc)

- Isometric movements – Bilateral & Unilateral (Iso RFE Lunge, Iso BW Squat, etc)

- Locomotor Skill Development

- Deceleration tasks following acceleration such as the drill “Acell & Decel closed skill” here https://elite.deelysportscience.com/sc/

- Reaction games which require controlled deceleration in an appropriate time.

- Reaction games that require rapid, controlled deceleration as quickly as possible such as the “Reactive COD” drill here https://elite.deelysportscience.com/sc/

It is vital to understand that we must develop an athletes ability to decelerate correctly and in a controlled manner before we put them under change of direction tasks. The precursor to every COD task is deceleration, which means if we cannot decelerate well we will be unable to change direction well. Jonas Dodoo (Speed Works Training) delivered a very interesting webinar on the topic of deceleration which you can find on his website.

Jonas also discussed mechanics on Episode 15 and 16 of our podcast which you can listen to here – https://linktr.ee/deelysportscience

Develop deceleration technique and ability first, COD second

Change of Direction

Note: While there is ongoing discussion with regard to the difference between COD (planned) and agility (reactive), for the purpose of this blog on the technique & development of changing direction we will discuss them as one.

As mentioned above, COD is a task that occurs in nearly every sport. The ability to decelerate, control and accelerate in a new direction is seen in cutting/stepping in rugby, chasing an attacker in soccer and transitioning from defence to attack in GAA. COD is a vital skill, and similar to deceleration, we must ensure that the athlete can complete the task efficiently.

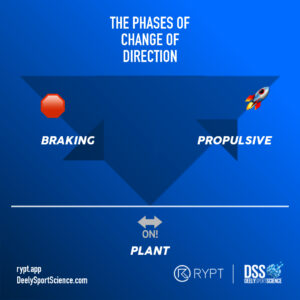

COD is a combination 3 phases:

- The Braking Phase (slowing down)

- The Propulsive Phase (re-accelerating)

- The Plant Phase (transitioning from braking/eccentric movement to acceleration/concentric movement)

Researchers argue the effect of strength and power training on the improvement of COD performance, with a 2008 meta-analysis stating that “exercises which more closely mimic the demands of COD, such as horizontal jump training (unilateral and bilateral), lateral jump training (unilateral and bilateral), loaded vertical jump training, sport-specific COD training and general COD training” have a greater impact on the performance of COD (Burghelli et al, 2008). We have further developed our understanding of the task since this review, with new studies stating that although previous studies found no improvement in COD ability following strength & power training, what those studies were testing for may not have been valid measures of COD ability (Nimphius et al, 2017)

In support of the above, we know that deceleration immediately precedes COD and the strength training that would improve our deceleration ability (detailed above) will also improve our COD ability. When we break it down, COD is a reactive, eccentric-to-concentric task and so improving strength, control and power in all those attributes would serve to improve our ability to complete the task of COD. However, as it is reactive there is also the need to develop and perfect our neuromuscular control in order to maximise the time in which COD can occur efficiently.

Rich Clarke of the UKSCA also lent his expertise in the area of COD on episode 7 of our podcast available here – https://linktr.ee/deelysportscience

Training to improve COD ability

*Deceleration improvement training as above

- Eccentric bilateral & unilateral movements – linear and lateral (Front Squat, SL Squat)

- Concentric bilateral & unilateral movements – linear and lateral (Deadlifts, Side Lunge etc)

- Isometric bilateral & unilateral movements – linear and lateral (SL Hold, Iso Lunge)

- Reactive/Plyometric bilateral & unilateral movements – linear and lateral (Pogo hops, drop jumps)

- Acceleration technique and ability

- Planned COD to develop technique and coordination

- Reactive or unpredictable COD to challenge technique and coordination

Conclusion

Deceleration and COD come hand in hand in a lot of sports, and so the development of an athletes efficiency in both task is vital. An important consideration for coaches when developing these skills is the athletes uni/bilateral eccentric, concentric and isometric strength. Technique is king at all times, but as these tasks can often require the athlete to control forces varying from 1.5 to 2 times their bodyweight, it is important that the neuromuscular system is also able to handle such force to minimise injury risk. Focus should absolutely be placed on developing deceleration & COD in training, progressing from controlled, planned scenarios to more chaotic, unpredictable scenarios with stimuli in order to replicate performance-like situations.

References

AthleticPerformanceToolbox net, 2017 – “Deceleration” by Jeremy Shepard

https://athleticperformancetoolbox.net/speed-and-agility/deceleration

Harper, D.J., Carling, C. & Kiely, J. High-Intensity Acceleration and Deceleration Demands in Elite Team Sports Competitive Match Play: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Sports Med 49, 1923–1947 (2019).

Hewit, Jennifer MSc, CSCS; Cronin, John PhD; Button, Chris PhD; Hume, Patria PhD Understanding Deceleration in Sport, Strength and Conditioning Journal: February 2011 – Volume 33 – Issue 1

Nimphius, S., Callaghan, S., Bezodis, N. and Lockie, R. (2017). “Change of Direction and Agility Tests.” Strength and Conditioning Journal, p.1

Simplifaster.com, 2018 – Key Concepts in Preparing for Agility and Change of Direction” by Matt Kuzdub.

https://simplifaster.com/articles/agility-change-of-direction/

DSS Online Training

We are now currently offering online training tailored to individual needs.

We are offering varying pricing strategy which are outlined within the following link: https://elite.deelysportscience.com/dss-online-training/

This training support includes:

This support will be provided to you through the RYPT app. A fantastic resource for online training allowing top performance coaches to send programmes directly to your phone each week.

The App includes:

(To find out more visit their site at: https://www.rypt.app)

To gain access to a 2 month free trial to the RYPT app – click on the link here:

https://portal.rypt.app/signup/86ACD9F

No Comments